An aquatic garden, a film-set landscape, and more: Four fanciful transformation plans, commissioned by Curbed.

By Justin Davidson

[Posted 5-3-21 on curbed.com]

What does Governors Island want to be when it grows up? That question has slouched around the place for a couple of decades now, frustrating officials who would like to see the place gainfully employed. All that empty land unbuilt, those stunning views unmonetized, the constant demands for public funds — the island is basically a moocher, and thank goodness. For now, it’s still a ghostly, magical chip of land that seems to have escaped from Manhattan and floated off into the harbor. Sea-salted breezes glide over freshly mounded hills, which offer views of young trees, old buildings, and, beyond the encircling bay, a ring of greenery, gantries, copper, and glass. But there is some big-time development in the offing, which makes me wonder: Can that fragile mixture of separateness and proximity — that pervasive sense of islandness — withstand a major real-estate venture?

The plan that’s making its way through the approval process calls for a center dedicated to fight climate change, or, more grandly, “an ecosystem for climate solutions,” as Clare Newman, president and CEO of the Trust for Governors Island, describes it. The proposed rezoning would, Newman says, summon “a research institution, surrounded by green tech start-ups, design firms, dorms, and faculty housing.” (Since Columbia has just established its own climate school, it would presumably either be part of the university or compete with it.) An island that once hosted military personnel sworn to protect the nation would now buzz with scientists, engineers, designers, and techies working to protect the planet. Or, to put it another way, Newman is hoping for a collection of buildings containing more square footage than One World Trade Center (4.275 million, to be precise), including a couple of big honking towers, up to 25 stories tall. All this on an island that rising seas appear determined to swallow; the climate center can study its own drowning.

The Trust, charged with making the island pay (for its own upkeep, at least), is trundling along the well-paved road of large-scale development on public sites. Step one: identify possible tenants, preferably big institutions, and privately ask what they need. Then, tailor the zoning to match their interest and shepherd the result through public approval. Finally, invite proposals from the people who helped set the rules. Maybe the result of this closed loop will be as wondrous in its architecture as in its aspirations. Maybe we’ll get the fresh approach that Governors Island’s vulnerability deserves, with architecture not just serving as the aesthetic trim on a multibillion-dollar investment but as deep thinking of a kind that should precede the first rule. If we are going to use it as a place where humans can learn to protect themselves from their own worst instincts, we should start by valuing — and expressing architecturally — the relationship between building, park, water, and the urban complexity beyond. Forgive my skepticism: In the past two decades, New Yorkers have watched several ostensibly noble blank-slate megaprojects take shape — the World Trade Center, Hudson Yards, Cornell Tech, and Columbia’s new Manhattan Valley campus — and they all wound up looking like they were put together from the same kit of parts by the same small club of architects. But we don’t have to keep reaching the same foregone conclusions. Instead of arguing over how high our towers should go and what kind of glass gets stuck to the outside, we should use the laboratory of Governors Island to discover there is more architecture in the world than is dreamed of in our cramped philosophy.

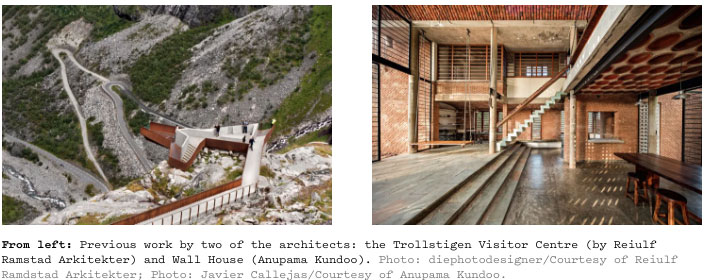

And so, in pursuit of a way to preserve the island’s openness and horizontality, I got in touch with four firms whose works I admire for their ingenious fusions of design and nature: Anupama Kundoo from India, Estudio Macías Peredo from Mexico, Barbara Bestor in Los Angeles, and Reiulf Ramstad from Norway. They have built their practices in dramatically different cultures of design and construction. In India and Mexico, architects design around minimal budgets that are more efficiently spent on labor than on imported materials; craftsmanship takes precedence over factory-made modules shipped from half a world away. In Norway, the government has a long-standing program of commissioning architecture that is knitted to the nation’s natural marvels. Los Angeles lays a byzantine set of seismic, zoning, and preservation rules over rocky and hugely expensive terrain. Despite their differences, all these architects understand the dynamic between what they do and the environment they do it to. Ramstad predicts that “in the future, the role of the architecture can be not just to urbanize but to renaturalize” — the kind of statement that wrinkles the noses of developers, investors, and government officials focused on a city’s most urgent needs. But for cities to adapt to a changing climate, they will have to learn to “tread carefully and with restraint,” as Kundoo puts it. Not every urban problem can be treated by administering knockout doses of concrete and steel. I didn’t ask the architects to address the problem the Trust has posed: how to leverage empty land to keep the infrastructure in good shape without depending on municipal largesse. Yet most of their proposals, conceptually at least, are compatible with the study of climate change. If you really want “an ecosystem for climate solutions,” start with architects who understand ecosystems.

What I Asked For

The northern core of the island is the city’s cradle, where Lenape people and and later Dutch colonists settled beneath a stand of nut trees before they decamped to Manhattan. And yet as recently as two decades ago, I was only dimly aware of Governors Island, then a Coast Guard outpost off-limits to civilians. Most New Yorkers shared my ignorance. The Reagan-Gorbachev summit that started winding down the Cold War took place there in 1988, which only added to its militarized mystique. In the mid-1990s, the federal government decommissioned the base and turned most of the island (except for a small national park) over to local control. When I first visited, in 2003, I found relics of the recent past (a decommissioned Burger King, a silent bowling alley) and sturdier 19th-century structures moldering poetically within sight of sparkling skyscrapers. Soon came futurist fantasies. The architect Santiago Calatrava offered to stitch New York’s archipelago together with an aerial tramway that — in optimistic renderings, anyway — resembled a trace of Spider-Man’s web glinting against the skyline. That idea, and so many others, died. Instead, the Harbor School moved into the old infirmary building, and now more than 400 kids take the ferry to class, soon to be joined by 400 more.

The southern section is an artifice made of millions of cubic yards of dirt hauled up from the construction of the subway system more than a century ago. With no neighbors to evict or appease, and scant architectural character to protect, it is as close as you get in New York to a blank slate. Day-trippers have shaped the park simply by using it. Where they chose to picnic became a picnic spot; where they dozed, a grove of hammocks. (These days, a million visitors step off the ferry every year — 10,000 on an average weekend day in summer.) The Dutch landscape architecture firm West 8 laid out a new park through the middle of South Island and recycled the rubble from demolished barracks into a range of mini-hills, endowing the flats with new topography. Meanwhile, two development zones, a pair of gray areas shaped like hot-dog rolls, sandwiched the new park, waiting to be filled.

I thought I knew what should go there: a scattering of spare small structures sensitive to weather, water, and light. Some years ago, I made a pilgrimage to Álvaro Siza’s Boa Nova Tea House, from 1958, which hunkers low among the rocks on the coast outside Porto, Portugal. The shingled roof swoops down over the restaurant’s white walls and grand windows, shading them from the glare. Inside is a symphony of wood and shadows. I called the Trust’s president at the time, Leslie Koch, and urged her to hire Siza to design a New York sequel as his U.S. debut. (It didn’t happen.) Then, in the summer of 2019, I saw the Xylem wooden pavilion that the Burkina Faso–born German architect Francis Kéré tucked into a culvert at the Tippet Rise Art Center in Montana. Bundles of upright lodgepole and ponderosa logs are suspended overhead like organ pipes, casting a dappled shade. Again, I wanted one for Governors Island. When I first contacted Kundoo, Macías Peredo, Ramstad, and Bestor, I thought they might each sketch their own version of a Boa Nova or Xylem — some exquisitely crafted folly, café, pavilion, or shed.

What I Got

I had underestimated the architects. Instead of fussing with the design of a small structure, they all zoomed out to get a sense of the context and the island’s climate destiny. Instead of showpieces, they designed, yes, ecosystems. Each independently extended the idea of constructed nature, sharply demarcating the low landfill from the existing, and slightly raised, historic district. Each blurred the division between land and encroaching seas. But if the approaches are similar, the results are distinct.

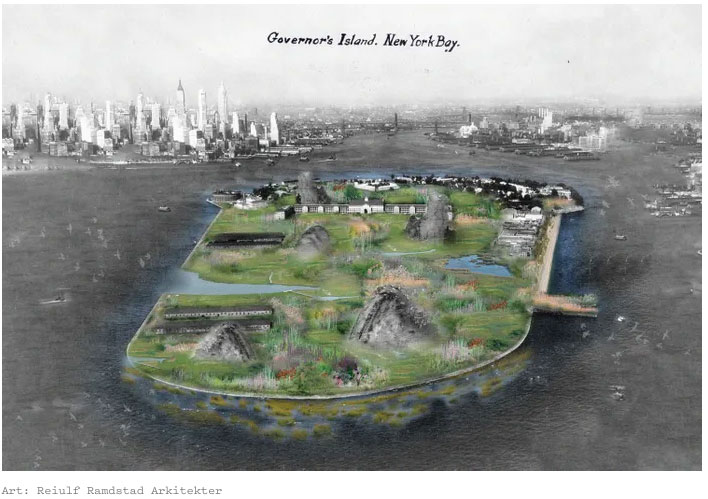

Reiulf Ramstad Arkitekter (Oslo)

What first drew me to Ramstad was a roadside rest stop like a man-made mountain range, nestled in the Norwegian pass called Trollstigen. The building sits low to the rock and sprouts tendrils — concrete ramps, terraced pools, glass railings, and balconies cantilevered far above the fjord. The effect is at once spectacular and self-effacing, inviting visitors to immerse themselves in the jagged landscape rather than stand back and ogle the architecture. I suspect most passersby remember the view but not the platform. At Governors Island, Ramstad proposes to transform the island into “an archaic landscape,” guiding it toward a wilderness that never actually existed. “It ought to contrast with the rest of Manhattan, answering its density of buildings and residents with different forms of density: colors, smells, and sounds,” he suggests. He would sweep away the non-historic structures, leave some ghostly ruins, and create a new topography of marshes and micro-mountains. “Architectural installations should be extremely simple and made out of organic materials,” he suggests. “Maybe just a shed you can visit.”

Anupama Kundoo (Pune, India, and Berlin)

Kundoo, too, has developed a strategy for “restoring” the island to a primeval state that never actually existed here. She sees Governors Island as an experimental preserve, a platform for studying urban nature, where the rules of postindustrial capitalism are set aside and replaced with a communal spirit of cooperation. “I look at human beings’ time as a resource that we can use rather than something that needs to be saved. What have we done with all the time we saved? Let’s let people give it. They’ll create happily, and the result will belong to all of us. It sounds utopian, but I learned that in India. If I were to wait for money, I’d be doing nothing. But if you have nothing, you still have your own time, and you can use that.” That idea has been a theme in her architecture for 30 years. Kundoo has built most of her work in the utopian planned city of Auroville, India, not a shining apparition like Oscar Niemeyer’s Brasília, all white concrete and empty space, but an evolving community of brick, sticks, and stone, threaded through dense vegetation.

In the catalogue to an exhibition of Kundoo’s work at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, the critic Edwin Heathcote writes about her affection for handmade brick, “the mechanism by which architecture is extruded from the earth … Kundoo calls it the oldest mass-manufactured building material in the world.” Brick has a storied place in the architecture of the Northeast, too, and it’s easy to imagine Kundoo’s mixture of modernism and ancient craft fitting in with the rust-colored Victoriana of Colonels Row. Just as, for a time, the Cathedral of Saint John the Divine ran a stone-carving school, Governors Island could build on Brooklyn’s love of all things artisanal and train volunteers to make and lay bricks by hand.

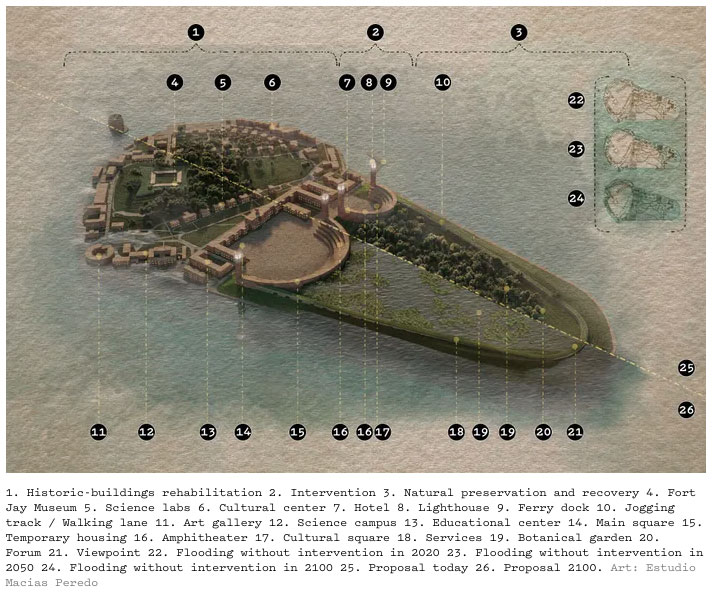

Estudio Macías Peredo (Guadalajara, Mexico)

The Guadalajara-based firm of Macías Peredo began its research by going straight to the maps of flood projections and found that in the coming decades, the low-lying landfill will lie even lower and be filled in with water. Its solution is to leave the southern part of the island as an “aquatic botanical garden” and protect the historic district with a curving structure that is built into a berm on one side and, on the other, outlines a semi-circular plaza anchored by a pair of tall, thin campaniles (marked 26 and 27 on the renderings above). “We’re making a new fort to protect the landscape itself,” says one member of the firm, Diego Quirarte. “The outline of the original island is a memory that has always been there. The important part is the space formed between the new and old buildings.” That public space acts as a portal between urbanized New York and the quasi-natural world, the modern megalopolis’ version of old city gates.

Bestor Architecture (Los Angeles)

Bestor sees the island as a way for New York to supercharge its film production with L.A.-style back lots that are also attractions and public space. “In Los Angeles, the production business inhabits big swaths of land, and it’s created this hybrid urban landscape. What if you had real public space mixed with landscape you could shoot in?” Bestor says. Large, simple sheds like airplane hangars would be flanked by, say, a dusty 1880s Main Street or a block of downtown Singapore: The architectural style might change according to a production’s needs. But instead of sequestering these areas off behind studio walls, they would be stitched into the fabric of the city, much as a brownstone block in Brooklyn becomes a set for a day or two, then reverts to its year-round use. A lagoon used to shoot beach scenes could double as a public amenity. A large outdoor performance venue is moored on the water the way the Bregenz Festival’s stage floats on Lake Constance in Austria. And interspersed among these revenue-generating structures are allotment gardens, serving NYCHA residents and other apartment dwellers who would otherwise never get near a patch of fertile dirt.

The worth of these proposals doesn’t stop at the island’s edge. Bestor, Ramstad, Kundoo, and Macías Peredo stand in for a global army of talented and resourceful designers that New York ignores in favor of a restricted stable of marquee firms, corporate behemoths, and journeyman service providers. One element of making a city more flexible and diverse is to diversify its design culture. Instead of subjecting a special place to the overpowering force of real-estate habit, New York could use it to cultivate a new architectural openness and refresh its repertoire of traditions.